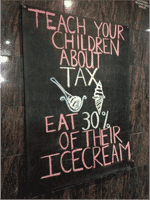

The Chartered Institute of Taxation is pushing for children as young as 5 to be taught the trials and tribulations of the taxman. Should we protect the innocent, or warn them of things to come?

Now I don’t know about you, but when I was at school, the concept of tax was something I cared very little about, and understandably so. To me it was something that my Dad would often moan about, but then again so were Duran Duran, so I reasonably gave it little thought. How was I to know that I would one day curse the name of the taxman every time I looked at a statement or timesheet?

“All school children should take part in compulsory lessons on taxation, so they can understand how it works, why it is necessary and what their obligations will be once they leave the classroom.”

This quote backed by the Charted Institute of Taxation, as well as bringing to mind the image of classrooms full of mini Alan Sugars, poses an interesting thought. It can be argued that the children of tomorrow would no doubt benefit from understanding tax before they are unleashed into the professional world, but despite this, tax laws and legislation are far from a compulsory subject.

Issuing the recommendation, the chartered institute added that it was “very disappointed” that within the recent national curriculum, educating 5-to 16-year-olds about taxes was not on the list of priorities. “Tax is one of the least understood areas of personal finance” argues the Institute, commenting on the inclusion of teaching ‘financial skills’ to youngsters whilst still leaving tax out.

“Most school children will one day become employees when they will need to be able to understand a PAYE coding notice or payslip and to be able to identify when it is wrong,” contended the Institute’s President Stephen Coleclough. “Many will go into business where tax is a key cost and administrative burden that cannot be ignored. An understanding of taxation – how it works, why it is necessary and what the obligations of the taxpayer are – is an essential part of financial education.”

Coleclough certainly provides a convincing argument, as from experience, breaking into the world of payslips and bank statements is hard enough without having the ignorance of why a percentage of one’s hard earned wages is being taken hastily away. To murk the tax waters further, students who opt into further education, or those who turn to self-employment, are subjected to different tax systems than the PAYE professional, thus reiterating a potential need for ‘tax’ to be included into the modern curriculum.

“Tax may not be quite as enthralling as the rest of the population as it is for us… [but it should become] as familiar a feature of school education as Bunsen burner experiments and football.”

So should school children be taught tax? Maybe so, but could it perhaps be the parents who are ceasing ‘tax education’, who on some level want their offspring to enjoy life to the fullest before entering the taxman’s inescapable grasp.

Would this Institute of Taxation approved education include an explanation of how and why once you have paid tax, government then does its utmost to ensure your hard earned money is wasted as badly as is humanly possible to imagine?